I grew up in a Spanish and Mexican household—two cultures separated by an ocean and, honestly, by very different cuisines. There aren’t many dishes they have in common, but arroz con leche—rice pudding—is one of them. Sweet, simple, and familiar. I always thought of it as ours. What I didn’t know back then was that rice pudding is everywhere. No single country claims it. It belongs to all of us.

Now that I’ve been living in Cairo for a while, I notice it’s everywhere here too. Egyptians don’t just eat rice pudding—they live with it. They even have a handful of desserts with rice. And that’s what pulled me in. How did this beloved dessert end up here? And how did it become so deeply rooted in Egypt’s culinary soul?

There’s a kind of magic in Cairo—a city where even the simplest bowl of rice and milk carries the weight of centuries. Roz bel Laban isn’t just dessert. It’s comfort dressed in cream, a humble dish that tells the story of empires rising and falling, of trade routes and migrations, of sweet tooths spanning continents. Somewhere, steam rises off a battered tin pot, milk thickens around tender grains, and a sprinkle of nuts or coconut reminds you this was once a dish fit only for the wealthy, now beloved by everyone. You don’t need a silver spoon to taste the history—just an appetite and a little curiosity.

In Egypt, rice or roz, is not just an ingredient—it’s a way of life. Walk into any home, any street food joint, or any bustling kitchen, and you’ll find rice front and center. It’s the backbone of dishes like koshary—Egypt’s chaotic, comforting answer to hunger—where rice, lentils, pasta, and crispy onions collide in a perfect mess. Or mahshi, where rice, kissed by a blend of spices, finds itself snug inside grape leaves and zucchini. Or hamam mahshi, where tender stuffed pigeons are roasted until golden, their bellies packed with spiced rice that soaks up every drop of flavor. Then there’s fattah, the grand feast of layered rice, crispy bread, and slow-cooked meat, drenched in garlicky tomato sauce, a dish so indulgent it feels like a royal decree. Rice is everywhere, in everything, a grain that’s woven into the fabric of Egyptian cuisine. Though widely consumed in Egypt today, rice was a late arrival to its culinary landscape.

While some believe rice came during the early Islamic period, Professor Daniel Newman, Chair of Arabic Studies at the University of Durham, explains that historical sources only mention its cultivation in Egypt by the 10th century, particularly in Fayoum and Upper Egypt. Before that? No sign of it.

Rice pudding, however, boasts ancient origins. Versions like kheer appear in Indian texts such as the Mahabharata—dating back more than two thousand years. Medieval Arab cuisine, heavily influenced by Persian traditions, embraced it too. “Culinary literature from the Abbasid period—9th and 10th centuries—mentions rice puddings, which appeared in Iraq, Syria, and Egypt. These were elite dishes, sometimes made with ground rice, sometimes whole, often sweetened with honey or sugar,” says Professor Newman. They were enriched with rosewater, saffron, and nuts—flavors we still find in Egyptian sweets today.

Rice and milk have been mingling in kitchens worldwide for centuries. In ancient Rome, rice was so rare it was used more as medicine than food. Meanwhile, in Korea’s Joseon Dynasty (1392–1897), milk was an even rarer commodity, reserved for royalty, and used to prepare tarakjuk—a dish strikingly similar to rice pudding.

Closer to Egypt, the recipe journeyed through Persia and the Middle East, morphing into various forms before settling here. Professor Newman points out that rice entered Europe through Spain and Sicily, likely carried by Muslim rulers—and probably with the idea of rice pudding alongside.

Egypt’s version kept the silkiness and floral hints of its ancestors but made one thing non-negotiable: fresh milk. In both medieval Europe and Egypt, rice pudding had sweet and savory forms. “In Egypt,” Professor Newman notes, “some versions included shredded chicken—a tradition that still survives in Turkey today with dishes like tavuk göğsü.”

One chef helping keep this culinary heritage alive is Chef Moustafa Elrefaey, executive chef and cofounder of Zööba—ranked 21st in the MENA’s 50 Best Restaurants 2025. Chef Elrefaey recalls, “My grandmother used to make a savory version of rice pudding called roz me’ammar with chicken—very simple but very flavorful.” It’s a reminder that Roz bel Laban, like Egypt itself, has layers—of flavor, of meaning, of history.

As rice grew more common, Roz bel Laban found its soulful expression. Professor Newman explains, “Initially, rice was an elite product—three times more expensive than wheat—but by the 15th century, it became part of middle-class culinary traditions, even appearing as street food.”

Unlike elsewhere, where rice pudding stayed mostly homemade, Egypt developed a unique tradition: dairy shops dedicated to selling it. You can still imagine the medieval markets where milk merchants would serve bowls of warm rice pudding—just like some do today. It’s this deep relationship with dairy that truly defines Roz bel Laban.

Milk runs through every spoonful—more than an ingredient, it’s a marker of class, craft, and taste. “The wealthiest versions were prepared with milk,” Professor Newman explains, “while poorer versions would use water. It was a social marker.” Cow’s milk was considered superior, especially in cities, while sheep and goat’s milk filled in elsewhere.

That reverence for milk lives on. “I use a combination of cow milk and buffalo milk,” Chef Elrefaey tells me. “It gives you richness and a lovely flavor. Never canned, always fresh.” His method—cooking the rice directly in milk—preserves the grains, with sugar and vanilla added off the heat to keep the color and fragrance. A hint of orange zest brightens the whole thing.

“Egyptians prefer any dessert that contains milk,” he laughs, rattling off ashura, mihallabiya, belil—each a testament to dairy’s central role in our sweets. For him, Roz bel Laban is personal—memories of eating it warm, straight from the pot with his mother and grandmother. “There’s something special when it’s still warm, fragrant, with a gratin from the oven. That little bitterness from the top layer—it’s lovely.”

Centuries of refinement shaped the dessert we know now. Rice slowly simmered in milk, finished with rose or orange blossom water. It became the soft landing after a heavy meal, a Ramadan staple, a symbol of sweetness and abundance. It’s the dish grandmothers make with a knowing touch, the treat kids beg for, the midnight indulgence that soothes and satisfies.

What sets Egypt’s version apart is the sheer smoothness and intensity of the milk. Egyptians don’t overcomplicate it—they win you over with authenticity. And that milk? It tastes like milk should—rich, fresh, almost farm-like. It’s a flavor you don’t get in the Mexican, Spanish, or British versions, where the milkiness is often more muted.

Then there’s qishta—thickened clotted cream—folded in to deepen the richness and give Roz bel Laban its signature velvety texture. It’s that uniquely Egyptian touch few other rice puddings have.

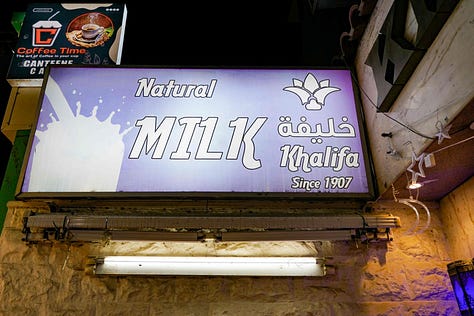

Walk through Cairo and you’ll find Roz bel Laban everywhere. El Malky—founded in 1917. Khalifa, established in 1907. Newer players like B.Laban, boasting millions of social media followers—a testament to how this humble dish keeps capturing new generations. These aren’t just dessert shops—they’re institutions. Behind every counter is a family recipe, passed down and fiercely guarded. A story of tradition, craft, and quiet pride.

And like everything we love, Roz bel Laban keeps evolving. Across the city, shops are experimenting—topping it with ice cream, Nutella, pistachio cream, Lotus cookies, mango purée, even chocolate drizzle. But somehow, these twists never stray too far from the heart of it. Roz bel Laban evolves, but it never loses its soul.

In the end, Roz bel Laban is Egypt in a bowl—humble, rich, layered with stories. A dessert that started as a luxury, sold in markets centuries ago, and now lives on in family kitchens and neon-lit dessert shops. It doesn’t just satisfy a craving—it carries a country’s history, its love for sweetness, its unapologetic indulgence.

Because in Egypt, even the simplest bowl of rice and milk carries a story.